Much ÖZETİ| has changed since the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on US soil, after which the country launched a so-called “global war on terror.”

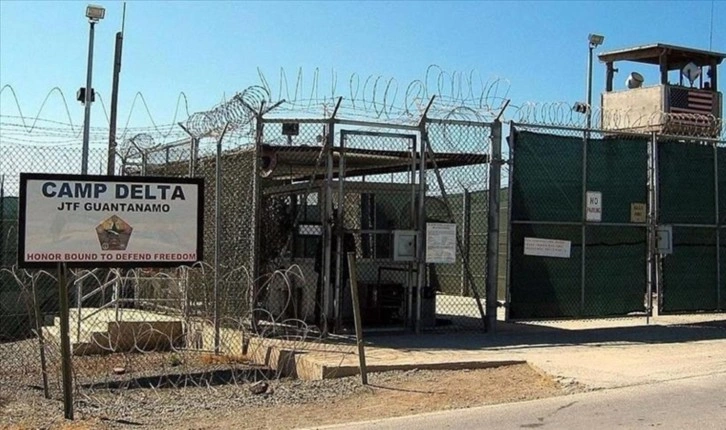

America withdrew its military forces from Afghanistan in August 2021, but the US military prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, which was created to hold terrorist suspects captured in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere, remains open.

The notorious prison was established 21 years ago today in Guantanamo Bay, which the US leased from Cuba for the navy in 1903.

Since then, the detention camp, also known as “Gitmo,” has held roughly 780 detainees, most of them without charge or trial, with many said to have gone through unspeakable horrors. Currently, 35 detainees remain and 20 of them are eligible for transfer.

Three of the 35 detainees are eligible for a “Periodic Review Board” while nine are involved in the “military commissions process” and three have been convicted in military commissions, according to the US Department of Defense.

Among the 780 detainees that were held at Guantanamo Bay include Mansoor Adayfi, 40, a citizen of Yemen who remained imprisoned for nearly 15 years.

He was handed over to the CIA in 2002, then an 18-year-old from Yemen who went to Afghanistan for research.

He was accused of being an Egyptian Al-Qaeda leader, although, at first, he was neither told about the charges, nor that he was being taken to Guantanamo Bay.

“I was in the black site, totally dark,” he recalled the first three months of imprisonment in Afghanistan’s Kandahar, where he said he was stripped naked and tortured.

Adayfi was later shipped to Guantanamo, and held without charge until July 2016.

“We had no idea where we were,” he told Anadolu in a Zoom interview from his home in Serbia, wearing an orange cloth around his neck, symbolizing his time at the infamous detention camp. “They never told us about the charges or why we were there."

When the US authorities decided that he poses no threat to the country, they sent Adayfi to Serbia.

“So basically for 15 years, I guess it was a [case of] mistaken identity,” he said, summarizing his incarceration.

Why still open?

Guantanamo Bay has been at the center of US politics over the years.

Former President Barack Obama promised to shut down the prison facility, but that did not happen as he met with stiff opposition in Congress.

Ex-President Donald Trump decided to keep the controversial prison open, and called for an immediate halt to detainee transfers. Only one Guantanamo prisoner was transferred under his administration.

In his first weeks in office, President Joe Biden announced his intention to close the prison camp, but to no avail.

Last month, Biden had to sign into law a $770 billion defense bill, which included provisions that could make it impossible for him to shut down the facility, such as barring the use of funds to transfer detainees to the custody of foreign countries.

“I urge the Congress to eliminate these restrictions as soon as possible,” Biden said in a statement as he signed the bill but criticized the restrictions.

According to Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham University School of Law, the Biden administration is “taking some very active steps” into the closure of the prison.

The Biden administration last September appointed a new special representative, Tina Kaidanow, to oversee the transfer of detainees, Greenberg noted.

“So I'm hopeful that they will close it. I think they have to keep the aggressive pace that they started with,” she said.

“Guantanamo was a mistake. It was created to exist outside the law and has kept people without charge for 21 years.

“We failed to try the individuals accused of the attacks of 9/11 to have a trial for them, which is unfair to the victim's families as well as unfair to the defendants themselves,” she added.

Transfer of remaining prisoners

Clive Stafford Smith, an international human rights lawyer who represents four Guantanamo detainees after securing the release of 83 prisoners over the years, said 20 out of the 35 remaining people in the prison were cleared and expects to “get some more people out soon.”

“When I get the current people out, I'm going to help on other cases,” he told Anadolu in a zoom interview from Gitmo, where he went to visit his clients.

“I think it's a blot on the American human rights copybook. And I don't think we should stop working on it until we've closed it down,” he added.

Although Smith does not believe Biden will close Guantanamo, he says "we must keep trying and keep pushing because it really is in no one's interest to have this place open.”

“We're currently spending over $14 million a year per prisoner, money that could be much better spent on health care for poor people. It's a total waste of money,” he said.

The latest transfer from Guantanamo was last October when Saifullah Paracha, a Pakistani businessman who was the oldest prisoner at the US detention center, returned to his native country after more than 18 years.

In response to Anadolu's questions by email, a State Department spokesperson said the Biden Administration "remains dedicated to a deliberate and thorough process focused on responsibly reducing the detainee population at Guantanamo Bay and ultimately closing the facility.”

The spokesperson said the State Department was seeking to identify "suitable onward transfer countries and negotiate transfer and resettlement agreements, including appropriate security and humane treatment assurances."

“The United States engages in an interagency review process that ensures that law of war detention is no longer necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to U.S. security,” the spokesperson added.

Former prisoners trying to take back their lives

Being transferred to a third country, and starting a new life after years of imprisonment is not an easy process for many detainees.

Adayfi, for instance, said he was sent to Serbia “against his will.” He refused to go because of his memories from the 1990s when Serbian forces massacred Bosnian Muslims.

He has not been able to meet his loved ones in Yemen due to the ongoing civil war, and has also not been able to travel outside Serbia since he does not have a passport.

Trying to get his life back together, he studied at a university in Serbia, where he wrote a thesis on the integration of former Guantanamo detainees.

In 2021, he wrote a memoir on his detention at Guantanamo Bay, Don't Forget Us Here, and spends most of his time advocating for the closure of the prison and the release of his "brothers" – other detainees still being held without charge.

“I think the first step we need to see is the release of those who have been cleared and if anyone have committed any crime they should be given a fair trial,” he said, calling on Biden to “close Guantanamo."

“We are calling for justice for everyone. 9/11 victims or the prisoners,” he explained.

Editor : Şerif SENCER